The story of Australia’s ball-tampering scandal has already been written, regurgitated and premasticated as events emerged in turn as basement comedy and then Attic tragedy. Warner, Bancroft and Smith were the foolish protagonists but, like Rosencranz and Gildenstern, they were agents of a rotten state not the architects of one. And like Tom Stoppard’s eponymous characters, they spent much time wholly bemused and befuddled as events unfolded at breakneck speed around them.

Cricket Australia off the pace

Cricket Australia looked as flat footed as Smith and Bancroft based on that first press conference held following stumps on the third day of the third Test at Newlands. Smith and Bancroft admitted the charge if not the methodology, brushing it off as a dumb thing to have done. Smith’s refusal to step down was de rigueur and so was his positive spin to move on and learn from the experience.

But those two blokes did not just turn up willy-nilly at the presser and extemporise. It was an admit-and-contain strategy that somebody in charge must have signed off. Darren Lehmann? Pat Howard? James Sutherland? Strewth, maybe it was Malcolm Conn? The incident required a quick response and the contrite-brazen-it-out approach looked to have been drawn from a well-thumbed scenario-manual that offered a template for the fuzzy route that had pretty much worked in the past.

Wink, wink – just don’t get caught

Except that day belonged to a different world. A world where ball tampering was accepted by the authorities as widespread and didn’t matter too much. MCC’s world cricket committee reviewed the current Laws in December 2016 and even after examining the complex issues raised by Faf du Plessis and Mintgate decided no changes were required. The ICC followed the MCC lead when revising its Playing Conditions from September 2017 and made nothing more than cosmetic, albeit possibly deeply flawed changes.

Cricinfo captured the muddled thinking when it reported that former Pakistan batsman Ramiz Raja, an MCC world cricket committee member, reassured players that it was less the practice that was the issue –

Mike [Brearley] put it absolutely brilliantly … You must not get caught. It is as simple as that.

This was a world where applying sugary saliva to a ball was OK but if the ball curator applied the mint residue in their mouth directly to the ball – as in du Plessis’s case – it was a chargeable offence. Because the sugar in the saliva was not mint residue, right?

It was also OK to apply these alchemies to the ball provided it was not captured by any of the 30 or so TV cameras standing sentinel around the grounds. It was a cheat’s charter. The challenge had shifted from changing the condition of the ball to not getting caught.

When the argument’s lost, there’s only the residue

In his 2008 biography Coming Back To Me, Marcus Trescothick revealed that during the 2005 Ashes, he worked his way through 15 Murray Mints a day, generating bucket-loads of sugar-sodden saliva, which “when applied to the ball for cleaning purposes, enabled it to keep its shine for longer and therefore its swing.”

Trescothick got away with it not because the practice was unknown or because he was better at prestidigitation. According to Trescothick, the practice was so central to the culture of the England camp that –

Once Phil Neale came on board as our operations manager it was one of his jobs to make sure the dressing-room was fully stocked [with Murray Mints] at all times.

Following Trescothick’s revelations, an ICC spokesman told the BBC–

According to the laws this [applying sweetened saliva to the ball] is illegal – but we won’t outlaw sucking sweets … It depends on the evidence and circumstances, so if something is brought to our attention it would be dealt with … But where do you stop, for example, if you start to try to stop everyone who is chewing gum?

Lawrence Booth on The Spin duties at the Guardian also in 2008 recalled Michael Atherton’s jolly anecdote in The Times earlier that year:

Cricketers of my era used sugar from sweets or chewing gum to good effect. During one Test at Lord’s the 12th man brought us sugar-free chewing gum, ensuring his 12th-man career was brief.

If anyone wishes to attempt a distinction between impulsive opportunity and pre-meditation, they should consider the long back story of ball tampering, institutionalised and readily accepted by national boards and the ICC. The supply of Phil Neale’s Murray mints and Mike Atherton’s 12th-man chewing gum were each calculated and premeditated. Trescothick’s finger will have introduced to the ball both sugar-enriched saliva and residue from the mint. Weaselly attempts by the ICC to make such nice distinctions are sleights that reveal a governing body that has tackled a known and endemic issue with a shoulder shrug and a turn of the head.

Here is an extract from my Mintgate article from back in November 2016 –

It is clear from this that Steve Smith is no stranger to the concept of ball tampering, but he is hardly head-butting the lines. Such is the ICC’s concern with what Matt Prior calls normal practice it has only ever charged Rahul Dravid (2004) and Faf du Plessis (2016) under the artificial substance provisions of Law 42.3 (a) (i) or any of its guises. Barely more have been charged under the old Law 42.3 (b).

As a Level 2 offence, ball tampering has an equivalence to time wasting – think Stuart Broad constantly re-tying his bootlaces – or a bowler running on a protected area. Even after Mintgate, the MCC and the ICC decided that ball tampering, as an offence, was correctly positioned within this hierarchy of misdemeanours.

In the aftermath of Mintgate, I warned that MCC had flunked an opportunity to establish clarity, and Michael Belief QC also failed, in his judgement on the du Plessis appeal, to provide a proper steer to the ICC on the absurd lack of certainty or leadership on the issue. In the end, du Plessis lost his match fee. He did not even miss one Test.

Faint signals from deep space, missed by the largest radio telescopes, have been stronger than the message sent out by the ICC. What hope for hapless cricketers seeking a small advantage that no one has ever proved to actually work and no one has ever said could cost them their career.

Turnbull turned it

When the scandal was first exposed, there was not the slightest notion that Cricket Australia had remotely transitioned from that old, cosy, muddled world to one where evangelical zeal held sway, demanding body parts be dipped in tar and nailed to sight screens across every State.

The intervention of an outraged premier Malcolm Turnbull changed everything. From that moment, ball tampering was no longer a barely policed Level 2 offence that led to occasional tuts and wrist-slaps. Seen through a political and commercial filter with sponsorship contracts to save and TV deals to secure it became a piss-boiling, heinous event that needed quick arrests, certain convictions and heavy sentences to reassure a nervous marketing community.

The process set out in Cricket Australia’s Code of Conduct seems to have been followed to the letter. Though the whole thing, from conduct to penalty, took just four days. One accepts that the early admission of guilt contributed to the speed of it all, but can anyone believe Iain Roy, Cricket Australia’s Head of Integrity (stop sniggering at the back), or James Sutherland, the CEO, properly reviewed or considered the circumstances, the context, precedent, proportionality or even natural justice? It feels as if they flew out to South Africa with One-Year Ban pre-printed on their luggage labels.

It is little wonder that Smith, Warner and Bancroft are likely to challenge the decisions with the full support of the Australian Cricketer’s Association. Others have written widely on what may be rotten in the culture of Australian cricket and Daniel Brettig has covered the subject brilliantly. The Sydney Morning Herald is also reporting that Cricket Australia’s top-down culture is going to be reviewed. Expect a softening of the penalties imposed on the fall guys and some resignations from the executive.

Faultlines in the ICC charges and changes

The bigger question concerns the failure of leadership offered by the ICC and the MCC. I forewarned that the MCC had misjudged its review of ball-tampering rules after Mintgate, and that the muddle and fudge would only make matters worse.

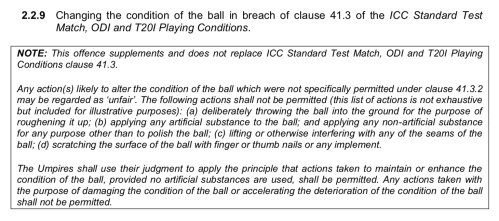

The ICC confirmed in its media statement that it charged Cameron Bancroft under Article 2.2.9 of the ICC Code of Conduct, which relates to “changing the condition of the ball in breach of [ICC Playing Condition] clause 41.3”

The ICC statement continues –

The umpires inspected the ball at the time and elected not to replace the ball and award a 5-run penalty as they could not see any marks on the ball that suggested that its condition had been changed as a direct result of Bancroft’s actions. The umpires though agreed that Bancroft’s actions were likely to alter the condition of the ball and he was therefore charges under Article 2.2.9.

There are a number of anomalies with this statement and the action that flowed from it. First, when Bancroft’s woeful attempts to alter the condition of the ball were captured on camera and replayed on the big screens at Newlands, the umpires intervened and questioned Bancroft. He produced his sunglasses bag from his pocket to suggest he had simply been using a soft piece of cloth to polish the ball.

It was nonsense of course, but they fell for it by all accounts. The Independent reported at the time – the two English umpires appeared satisfied with Bancroft’s explanation. Play was allowed to continue.

In my view, the ICC, in its statement, erroneously conflated two provisions. Clause 41.3 of the current ICC Playing Conditions requires the umpires, at the time, to consider if the player took any action which changed the condition of the ball. They decided that the condition of the ball was not changed. The ICC then compounded the error by bringing into play the likely to alter the condition of the ball note that is attached to Article 2.2.9 of the ICC Code of Conduct.

There are a number of problems with this.

First, Article 2 of the Code of Conduct explains that –

Where considered helpful, guidance notes have been provided in text boxes beneath the description of a particular offence. Such notes are intended only to provide guidance as to the nature and examples of certain conduct that might be prohibited by a particular Article and should not be read as an exhaustive or limiting list of conduct prohibited by such Article.

The notes do not define the offence. If there is a conflict between the notes and the articles, the articles take precedence, and both Clause 41.3 and Article 2.2.9 only refer to an offence being committed if the condition of the ball was changed. And it was not.

Secondly, MCC and the ICC may have made a hash of the ball-tampering provisions when they updated variously the Laws, Playing Conditions and Code of Conduct in late 2017.

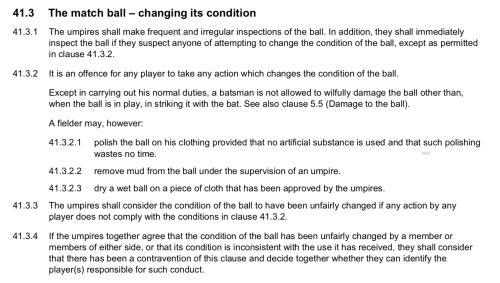

In 2016 (when the Faf du Plessis case was considered), Article 2.2.9 said it was a Level 2 offence to change the “condition of the ball in breach of Law 42.3 of the Laws of Cricket”. Here is what Law 42.3 said –

(a) Any fielder may

(i) polish the ball provided that no artificial substance is used and that such polishing wastes no time.

(ii) remove mud from the ball under the supervision of the umpire.

(iii) dry a wet ball on a piece of cloth.

(b) It is unfair for anyone to rub the ball on the ground for any reason, to interfere with any of the seams or the surface of the ball, to use any implement, or to take any other action whatsoever which is likely to alter the condition [my emphasis] of the ball, except as permitted in (a) above.

In 2017, Article 2.2.9 said it was a Level 2 offence to change the “condition of the ball in breach of Clause 41.3 of the ICC Playing Conditions. Here is what these say –

While the MCC has also sought to alide Law 42.3 (a) and (b) into a newly worded rule, the ICC has specifically changed its point of reference from the MCC’s previous Law 42.3 to its new Playing Condition Clause 41.3. The problem that MCC and the ICC have created is that Clause 41.3 omits the specificality of the old Law 42.3 (b), which relates to mechanical ball tampering with foreign objects or implements, for instance, sandpaper, and, more particularly, removes from the Law or the Playing Condition the expression likely to alter the condition of the ball.

The use of sandpaper was likely to change the condition of the ball under the old Law 42.3 (b), but, in the event, did not change the condition of the ball under the new Law/Playing Condition 41.3. The note to the current Article 2.2.9 is utterly discredited in this instance because a) it is a guideline only, b) it is in conflict with the stated offence, and c) it makes sense only in relation to the old Law 42.3 and not to the current Clause 41.3.

For these reasons, I am not convinced that Cameron was correctly charged and punished by the ICC, which needs to streamline and dovetail its Articles, Clauses and MCC Laws far more effectively.

Steve Smith was charged under Article 2.2.1 of the ICC Code of Conduct. This is a catch-all provision that is “intended to cover all types of conduct of a serious nature that is contrary to the spirit of the game and which is not specifically and adequately covered by the offences set out elsewhere in this Code of Conduct”. As Smith did not actually tamper with the ball himself, Article 2.2.9 did not apply. But his involvement in the conspiracy meant his was an offence not “specifically or adequately” covered elsewhere in the Code.

This gives us a window to the mindset of the ICC in terms of ball tampering. Articles 2.3.1 (Level 3 offences) and 2.4.1 (Level 4 offences) are also catch-all provisions. They mirror the equivalent provisions in Cricket Australia’s Code of Conduct that specifically define them as catch-all provisions. They relate to conduct that is respectively of a very serious nature and of an overwhelmingly serious nature not specifically or adequately covered elsewhere in the Code. The ICC, in full possession of the facts, chose to categorise the actions of Smith as serious but not very or overwhelmingly serious. Similarly, it could have thrown a Level 3 or Level 4 charge at Bancroft on the grounds that a Level 2 charge did not adequately cover the seriousness of the offence.

Blind and newly sighted

The governing body of international cricket was just as blind to the seriousness of events as Smith and Cricket Australia were at the press conference following stumps on day three of the Test. The ICC totally failed to grasp or anticipate the maelstrom that was about to unfold. It employed the same lazy, everybody-does-it-but-don’t-get caught muddle that it’s adopted for years. And then passed the problem to Cricket Australia.

David Richardson, CEO of the ICC, having both missed and dismissed the opportunity to change attitudes to ball tampering after Mintgate has now had a belated epiphany –

We’ve come to realise that the world — not only Australia — regards ball-tampering in a very serious light. It goes to the spirit of the game.

I must admit this has been an eye-opener for me personally. We need to look at the penalty imposed, specific to ball-tampering.

Around the world, ball-tampering is considered cheating… I think we need to look at it again, and this is what has prompted this review.

Well it is all very well being an eye opener for Richardson. Little comfort, I imagine, to Smith, Warner and Bancroft, disproportionately punished for conduct that the ICC now openly admits it never fully realised was even an issue.

Smith’s and Warner’s actions were crass and showed unacceptably poor judgement as skipper and vice-captain. But let’s be clear, father to their actions was an ICC that has consistently abrogated its responsibilities to establish clear, practical and science-based rules on ball handling. It has failed to police the rules, even as they stand, with rigour or consistency. And now it has failed to take responsibility for creating the woolly world of fudge-fudge and nudge-nudge that has contributed to the downfall of folk who could have been legends. When we consider the failings of the leadership group, let’s look beyond the Australian dressing room.

@Tregaskis, April 2018